Glutamate plays an important role in digestion by increasing salivation, signaling that a meal contains protein, and fueling the cells of the GI tract.

Ever wonder what happens to MSG in the body after it’s eaten? Let’s take a look at the journey of MSG through your digestive system.

For background, glutamate is the most abundant amino acid found in nature, and is one of twenty amino acids that make up proteins.

Glutamate is also made by the body as part of normal metabolism. The body makes about 50 grams of it a day, and stores about 4.5 pounds of it in major organs like the liver, kidneys, and muscles.

Our bodies get glutamate from food too. The average person eats about 10 to 20 grams of glutamate each day. This glutamate comes mostly from protein-containing food.

It can also come from seasonings like MSG (monosodium glutamate). MSG is an isolated, purified form of glutamate. Glutamate added as seasoning accounts for less than 10% of our daily glutamate intake from food. And according to the FDA, “a typical serving of a food with added MSG contains less than 0.5 grams of MSG.”

The Effects of MSG on the Digestive Tract

When you eat food containing glutamate – either from protein or seasoning – this is what happens:

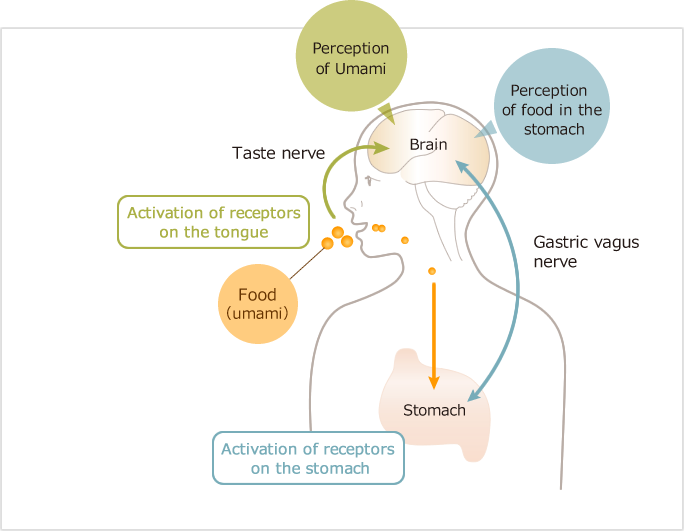

Mouth. Once you take a bite of a food that contains glutamate, the glutamate receptors in the mouth activate. They tell your brain that you are tasting umami, a meaty savory flavor. Your brain responds by telling your mouth to make more saliva. Saliva lubricates our food for swallowing.

Stomach. From the mouth, glutamate travels as part of the bolus of food down the esophagus to the stomach. There are glutamate receptors in the stomach as well. These activate the vagal nerve, which tells the brain that protein-rich foods have arrived. The brain responds by telling the stomach to prepare for protein digestion. Interestingly, the vagal nerve is activated only by glutamate, not any of the other amino acids.

If the glutamate is part of a string of amino acids (otherwise called a protein), enzymes break the protein into smaller parts. If the glutamate was already free – as would happen if the glutamate came from an aged or ripened food or from MSG – then it does not need to be broken down any further.

Small intestine. After leaving the stomach, glutamate enters the small intestine. If the glutamate was part of a protein, protein digestion will be finished in the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum), and all of the individual amino acids will be floating around waiting to be put to work. If the glutamate was already free, then it is ready to be used. All glutamate, regardless of the source, is treated by the body in the same way.

Over 95% of the glutamate eaten is then used as fuel by enterocytes, the cells that line the inside of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. That means it is mostly used up within our GI tract and not absorbed into the rest of our systems.

Finally, any remaining glutamate is absorbed into the bloodstream and delivered to cells to be used for metabolism or to make proteins. While a tiny amount of the glutamate that is eaten enters the bloodstream, blood levels of glutamate remain fairly stable.

And, that’s it! That’s how our bodies digest and use glutamate.

So, in summary, glutamate is the amino acid responsible for the flavor of umami. It’s found naturally in a variety of foods and can also be added by seasoning foods with MSG. MSG is processed by the body in the same way naturally occurring glutamate is, and glutamate plays an important role in digestion by increasing salivation, signaling that a meal contains protein and fueling the cells of the GI tract.