“Umami also has another profound attribute I had not appreciated as a child: It went unrecognized and unappreciated by Western culture, but eventually overcame that bias and discrimination by simply demonstrating that it has universal, human appeal.”

— a report by NPR, written by Yuki Noguchi, NPR.org/Health, September 12, 2023. Yuki Noguchi is a consumer health correspondent, science desk, at National Public Radio (NPR).

Excerpts from this report:

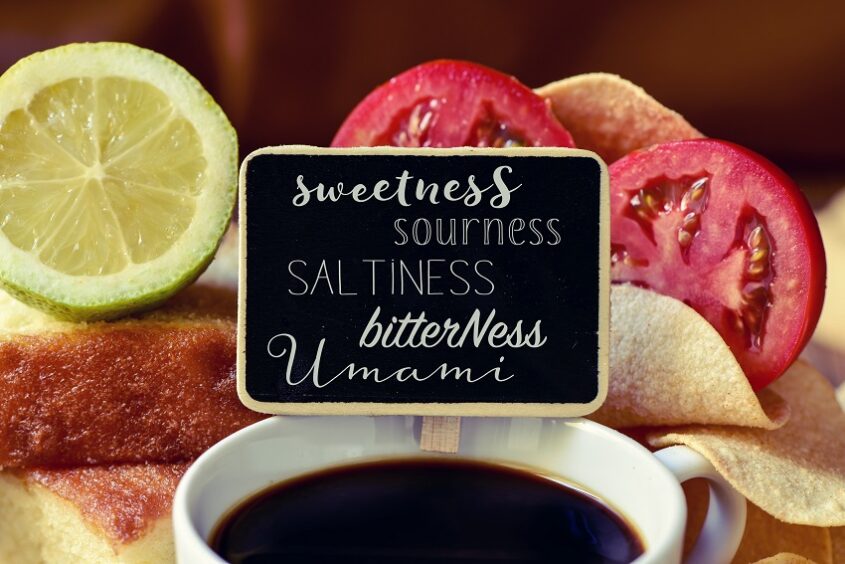

“I didn’t know what umami was, exactly; I thought of it like a magical elixir, the culinary hero pumping up food’s ‘yum factor.’ It’s savory and salty, like a ramen made of long-simmered bone broth. It can also have tang, like marinara sauce sprinkled with Parmesan, or ranch-flavored tortilla chips. It seemed so central to describing deliciousness itself, it seemed odd that English would have no equivalent word.

“But it would take nearly a century — and the discovery of glutamate receptors on our tongues two decades ago — before Western cultures accepted umami as a primary taste.

“That resistance, Spence says, is rooted in discrimination. ‘[There are] racist undertones that it came from the East,’ he says, which meant Western scientists and chefs were slow to embrace it. He says that legacy still powerfully shapes consumer perception today.

“Soon after its discovery, a Japanese company started marketing a salt-like additive that delivered an umami punch, monosodium glutamate, or the notorious MSG. That notoriety stems from a persistent, 50-year-old myth that MSG used in Chinese restaurants causes headaches.

” ‘It’s a zombie myth that will not die,’ says John Hayes, a behavioral food scientist at Penn State. Hayes says many people still don’t realize that, despite its borrowed Japanese name, umami exists in all cuisines.”